Every time you go to a polling place to cast your vote or every time you are given maternity leave paid for by the government; and every time you take a day off to do errands or receive income support during a pandemic – try and remember that those benefits should not be taken for granted. And try and show your gratitude.

Granted, there is still a lot to improve and repair. However, when looking back at human history, in all that concerns social benefits we are “standing on the shoulders of giants.” That was how the great Isaac Newton described the privilege he had of enjoying the scientific breakthroughs achieved prior to his time. And just like the scientific revolution which had to endure prolonged birth pangs, the modern welfare state also did not emerge from the fields of freedom. An abundance of suffering and tears flowed in the river of the proletariat in the 20th century as tens of thousands of heroes and heroines – some well-known and others nameless – fought for the generations that would come after them. They paid a steep price so we could complain today, at the beginning of the 21st century.

For instance, if you had the ill fortune of being a Jewish or Italian immigrant in the United States in the early 20th century and needed to put food on the table, chances are that you would have had no choice but to work in one of the numerous sweatshops that filled New York City at the time.

The tips of countless pens have been worn down trying to describe what went on in the sweatshops of America many decades before they were relocated to other places, and primarily to the Far East. Men and women and boys and girls, most of whom were newly arrived immigrants, were forced to work 14 and even 16 hours a day, with no breaks and in deplorable conditions, while being subjected to exploitation and abuse by their employers. Those were the days of unbridled American capitalism, before the concept of ‘regulation’ came into being. It was a period when the robber barons, who are now usually called tycoons, controlled the U.S. economy – many years before Roosevelt’s New Deal and long before the advent of ideas such as social justice and gender equality as we know them today.

Clara Lemlich was a link in a chain of Jewish socialist heroines that was also comprised of Rosa Luxemburg, Emma Goldman, Rose Schneiderman and Pauline Newman, among others, who got us where we are today. Lemlich was born into an Orthodox family in Ukraine in 1886. Despite her parents’ objections, she learned how to read and write at an early age. And to earn money to buy books, she worked sewing buttons and gave private lessons. In 1903, following the Kishinev pogrom, her family emigrated to the United States.

Shortly after their arrival, Clara went to work to help support the family and found herself in one of the garment industry’s sweatshops, where over half of the workers were Jewish women – some only 14 years old and others even younger. During that period, the industrial sewing machine was put into use and the women laborers were required to double their production outputs, but for the same salary and in the same poor conditions. Lemlich, who had a highly developed sense of justice, stood out as a leader and began organizing protests against the long work hours and terrible conditions.

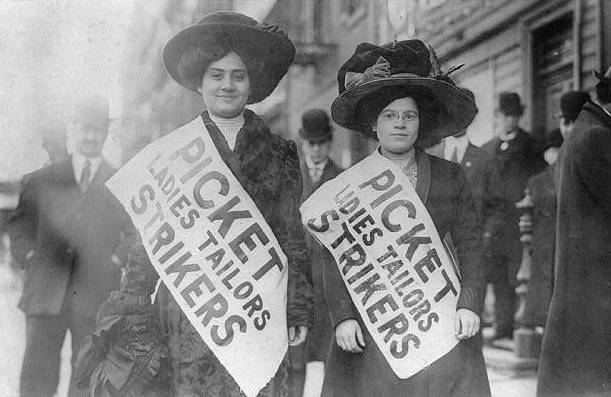

She first stepped onto the stage of history in September 1909 when she organized a strike at a shirtwaist factory after management refused to allow the male and female workers to unionize. To break the spirit of the strikers, the factory owners hired thugs and gangsters to brutalize the people on the picket lines. The six broken ribs that Lemlich came away with were one of the outcomes of the encounter with those thugs.

Two months later, on November 22, 1909 – 112 years ago this week – the ILGWU (International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union) held a rally attended by 20,000 local women wage earners. For two hours, Lemlich listened to uninspiring speeches by key figures in the American labor movement and socialist leaders from the Lower East Side of New York, who spoke about the need for solidarity and cohesion. True to her characteristic chutzpah, Lemlich took advantage of the intervals between the speeches to climb up on stage and proclaim in a loud voice: “I have listened to all the speakers and have no more patience for talk. I am a working girl. One of those who are on strike against intolerable conditions. I am tired of listening to speakers who talk in general terms. What we are here for is to decide whether we shall strike or not strike. I move that a general strike be declared now.”

Some people achieve fame and glory over the course of many years, and one woman achieved fame and glory in just one hour. Lemlich’s appeal spread like wildfire among the women workers. It led to an 11-week general strike in the garment industry, which became one of the seminal events in the history of the fight for workers’ rights in that industry, in general, and women workers, in particular. Following months of a bitter struggle, during which hundreds of strikers and demonstrators were tried and jailed, management gave in and entered into negotiations with the protestors. The agreement that was reached included a shorter work week of 52 hours instead of 65 hours and the workers were also given four paid vacation days. Additionally, a joint committee made up of management and workers was formed, who were entrusted with examining and arbitrating all future disputes between them. Public opinion – including that of satiated and materialistic America – sided for the most part with the women strikers. Clara Lemlich became a symbol and her persona provided inspiration for a number of novels and millions of working women.

The protest and the strike that followed it made an impact of historic proportions. For many years, they were viewed as precedential and totally transformed working conditions in the hyper-capitalist system that prevailed in America of the early 20th century. One example of that impact occurred in the men’s clothing industry in Chicago when 33,000 workers there adopted Lemlich’s model and went on strike. Led by Sidney Hillman, the strike lasted for four months until an agreement similar to the one reached by the women workers in New York was signed.

Lemlich was not, however, one to rest on her laurels. After being blacklisted from New York’s garment industry due to her pivotal role in the general strike, she redirected her energies and helped found a suffrage advocacy group among working class women. Over the years, she turned into what is now called a ‘serial activist.’ Other campaigns that Lemlich organized included a consumer boycott against kosher butcher shops that were taking advantage of their monopolistic position to charge excessive prices and a strike in protest of rent price hikes and the high cost of living. She was also instrumental in setting up a relief fund for women whose husbands were on strike and co-founded the United Council of Working Women, which later became an alliance of women’s organizations that proposed, demanded and formulated solutions for families during the Great Depression and economic crisis in the United States. Lemlich also pushed for and helped workers form unions wherever she went, including at the old age home where she later died at the age of 96.

The story of Clara Lemlich and the stories of hundreds of Jewish women trailblazers from across the globe are told at ANU – the largest Jewish museum in the world.