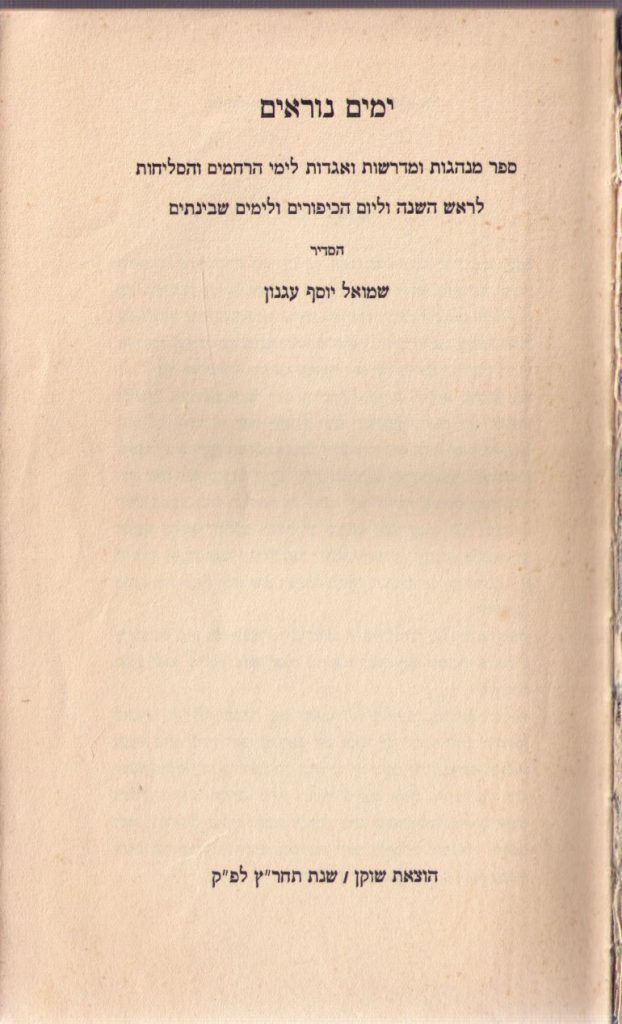

Everyone knows who Shai (Shmuel Yosef) Agnon is thanks to the fiction he wrote. But one of his best-known books, and perhaps his greatest and most ambitious undertaking, was actually an anthology – a compendium as that genre was called at the time – which was published in 1938. Agnon compiled and edited the anthology Days of Awe: A Treasure of Jewish Wisdom for Reflection, Repentance, and Renewal on the High Holy Days, whose Hebrew title is Yamim Noraim – High Holy Days – which can also be translated as ‘terrible days.’ It contains stories and commentaries dealing with Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and the ten days of repentance. It was commissioned by Schocken Publishing House in Berlin for the purpose of bringing the sacred texts of Judaism to a large readership.

In the preface to the book, Agnon cited the sources he made use of: “For the benefit of those who wish to be informed of the matters of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and the Days Between, I have assembled some sayings from the Torah and from the Prophets and from the Writing, from the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmud, from the halakhic Midrash and aggadic Midrash, and from the Zohar and from other books written by our Early Rabbis and Latter Rabbis, of blessed memory, and arranged them into three volumes according to the order of the days, each day and its matters.”

According to Agnon himself, he combed through close to one thousand books in order to glean the stories from them. But he did more than just gather. He also edited and rewrote them so the texts would be more palatable to people who were not used to reading sacred writings. In the advertisement that was published when the book was first released, it was described as “a book for everyone.” The advertisement enticed potential readers by promising that “those conversant in the sources will find priceless gems in Days of Awe, the likes of which they have never seen before because they are hidden in the secrets of ancient books that only expert researchers use.”

Agnon had more in mind than just making those texts accessible. He also wanted to add reading material for the High Holy Days, for the times between the prayers and services. In the preface he wrote to the second edition, the author talked about his childhood memories of going to the synagogue on Yom Kippur in Buczacz, the village in Eastern Galicia that he was born in. He also described how difficult and disappointing the transition was between the moments of chanting the sacred prayers and those of the idle talk that followed them before the praying resumed – and so much so that he would burst into tears as soon as the service would end. In Days of Awe, he actually tried to prolong those lofty moments and provide his readers with a bit of material that they could review and reflect on between the services.

To the dismay of his critics and to the great joy of his fans, Agnon took the liberty not only of choosing and editing which sacred texts would be included in the book, but he also added some original material. Many readers were not even aware that the Kol Dodi commentary, which was quoted in the book, did not actually exist and that Agnon wrote it himself. In an article he published in 1988, Chaim Stern wrote about the use Agnon made of commentaries as if they were original adapted passages. So how did Stern discover that? “In the course of our work, we explored the possibility of comparing one of those passages with its original source, until finding that Kol Dodi was nothing other than a pseudonym of the author himself.”

On the other hand, the researcher, Prof. Gershom Scholem, took pleasure in Agnon’s mischievousness and wrote the following: “With his caustic sense of humor, Agnon included a number of highly imaginative (and imaginary) passages, culled from his own vineyard, a nonexistent book Kol Dodi, innocently mentioned in the bibliography as a ‘manuscript in the possession of the author.'” (Source: Gershom Scholem, S.Y. Agnon – The Last Hebrew Classic?)

Shai Agnon emigrated to pre-State Israel for the first time in 1908. Four years later, he left and moved to Germany, where the philosopher, Martin Buber, helped him integrate into the Jewish community in Berlin and get a job at the publishing house, Jüdischer Verlag. In 1915, Buber invited Agnon to a gathering of Zionists at his home, where he was introduced to the businessman and Zionist philanthropist, Shlomo Zalman Schocken. Schocken was about ten years older than Agnon. When they met, Agnon was only 28 years old, whereas Schocken was already the owner of a successful department store chain bearing his name. Just like he had backed Buber’s career, Schocken decided to extend both social and financial support to Agnon as well.

Schocken became Agnon’s patron and confidante. And when Agnon emigrated to Palestine for the second time in 1924, he remained in close contact with Schocken, who stayed behind in Germany for a few more years. Schocken was the first to print Agnon’s books, even before he founded Schocken Publishing House in Berlin in 1931. For Schocken, the main purpose of his new business was to publish the works of his protégé, who was paid a regular salary so he could concentrate on his writing.

Schocken emigrated to Palestine in 1934. His publishing house continued to operate in Berlin until the Nazis shut it down in 1938. In the last years of its operation in Berlin, the publishing house was managed by the editor and designer, Dr. Moshe Spitzer, who had previously worked as Martin Buber’s research assistant. Spitzer stood at the helm of Schocken Publishing House during its final and difficult years, also serving as an editor and designer, before emigrating to Palestine himself. And like Schocken, he contributed greatly to Hebrew literature in Israel.

According to Motti Neiger in his book Publishers as Culture Mediators, which dealt with Spitzer’s tenure as editor of Schocken Publishing House, “Spitzer made sure to remain faithful to the spirit of Schocken Publishing House, which sought to introduce Jewish readers both in and outside Germany to the spiritual treasures of Jewish culture.” Spitzer “planned on publishing anthologies containing traditional literature which would speak to modern-day readers, in the spirit of Martin Buber’s work and in line with the policy defined by Schocken.”

Spitzer approached Agnon at the end of 1934 and suggested that he edit an anthology on the subject of the High Holy Days. Agnon, who by then was living in Jerusalem, took on the challenge during a period whose days were in fact terrible – Yamin Noraim, both in Palestine and in Europe. With riots by local Arabs plaguing the streets of the city, Agnon worked on the book from his home in Jerusalem’s Talpiot neighborhood. Upon completing it, he sent it to the publishing house in Germany. This was after the Nazis had already risen to power. Days of Awe was one of the last books released by Schocken Publishing House in Germany, and Spitzer managed to publish it in spite of Nazi censorship.

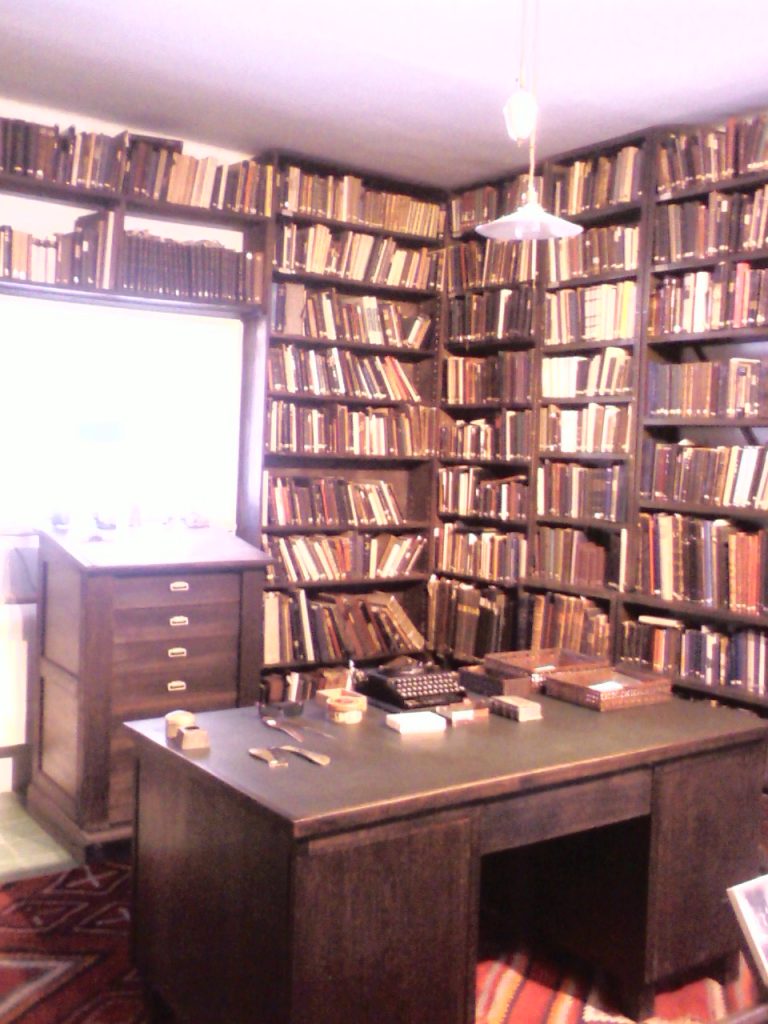

Agnon, who took the project very seriously, was assisted by an expert, Rabbi Shmuel Bialoblocki, who later founded the Department of Talmud at Bar-Ilan University. In the obituary that Agnon wrote about Bialoblocki in Haaretz in 1960, he described how their relationship became stronger while working on Days of Awe. A perhaps unintended byproduct of that obituary was the glimpse we received of the process whereby the book was written. “I was busy writing my book, Days of Awe,” Agnon recounted. “I worked on it sixteen hours a day for two-and-a-half years. I hardly left my house. Many weeks would elapse without me seeing the sun, except on Shabbats and holidays on my way to the Western Wall, or when I went into town to read some books. The book was already complete, but my heart was not completely at peace with the book. I feared that I may have failed in the matter of the Halakhic discourse, that I may have damaged something that I intended to repair, that in many places I had to fix the language.”

Bialoblocki joined the project only after Agnon finished writing the book. He brought him more sources, helped him to compare texts, and assisted in the proofreading and corrections. Nonetheless, Agnon still believed that the book had not been sufficiently proofread and was printed too hastily due to the political situation in Germany. There were in fact researchers who found errors in the book, even in its later editions. This was very distressing to Agnon, who was aware of the fact that the book had been printed with some inaccuracies. But despite the errors and Agnon’s frustration, the book was a big success and became popular reading material in religious and traditional homes during the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

The first edition of Days of Awe was printed in 1938 by Schocken Publishing House in Germany. It was only natural that Shlomo Zalman Schocken would make use of Haaretz, the Hebrew newspaper he bought not long before that, to promote the sale of the anthology. Chapters of the book were published in the newspaper, and free copies of the book were given as holiday gifts to subscribers. Additionally, a special limited edition of 40 copies was printed on special paper in Leipzig, which was described in Ohio State University’s Modern Hebrew Literature Lexicon as follows: “Forty copies of the book in this form were printed on Japanese paper, and this is the fourth printing of Schocken’s special printings of it.” Over the years, additional editions of the book were also published, and nowadays, as expected, it can also be purchased as an online book.

“The first time I opened Days of Awe, I felt as if I entered a room where a fascinating array of classical Jewish sources were having a lively conversation about Rosh Hashanah. That is how the American rabbi, Daniel Bouskila, described in the Jewish Journal the first time he read the English translation of Agnon’s book. “Talmudic rabbis, medieval Kabbalists, Sephardic philosophers, Hasidic rebbes and Halakhic scholars all seemed to be sitting around the same table. They came from different places and lived at different times, but the creative manner in which Agnon arranged them brought them to life in an interactive dialogue that transcended time and geography. Words that were originally spoken hundreds of years apart poetically flowed into one another. They shared ideas about Rosh Hashanah’s unique customs, its prayers, the power of repentance, the sounds of the shofar… When reading their words, I was transported into their world. I could hear their voices. It was as if Agnon had invited me into a timeless and ongoing Beit Midrash about the High Holy Days.”

That inclusiveness described by Bouskila forms the foundation of the book, which now stands alongside other works on the shelves of the Jewish bookcase. Additionally, it has helped bring secular Jews closer to the essence of the High Holy Days. That inclusiveness also makes Agnon’s Days of Awe a book that has relevance for readers today. “Days of Awe is not Sephardi or Ashkenazi, Hasidic or Mitnagdic, Halakhic or philosophical,” Bouskila wrote. “It’s all of those voices together, and many more, joined in harmony by Agnon’s literary magic.”