When the curation staff at ANU-The Museum of the Jewish People gave Shoshana Mandel, a textile conservator, the original robe and wig worn by Shloyme Mikhoels when he played the lead role in King Lear at the Moscow State Jewish Theater nearly 90 years ago – courtesy of the Israel Goor Theatre Archives and Museum in Jerusalem – she could hardly catch her breath.

Until the age of 10, Mandel lived in the Moscow State Jewish Theater compound. She was the only child of parents who were theater employees and remembers Mikhoels primarily as “Uncle Mikhoels” – a short and hyperactive man who spread warmth and love wherever he went. In 1956, Shoshana’s family emigrated to Israel under what was known as the “Gomulka Aliyah.” She learned about the tragic demise of the theater and its founders, including Mikhoels’s murder, only later as an adult.

Looking back, one could say that when it comes to Jewish memory, the underlying principle works more or less like this: tell me what ideological movement you belonged to and I’ll tell you if you’ll get fame and respect, or whether you’ll dive deep into the abyss of oblivion. We have all heard about Hanna Rovina, the first lady of Habima Theater, who won nearly every possible prize. But only a handful of people in Israel have heard about the actor, director and legendary cultural icon, Shloyme Mikhoels. The historical truth is that between the two world wars, Rovina and Mikhoels were the greatest stars of Jewish theater worldwide, whose center was in Moscow. In honor of Mikhoels’s 131st birthday, this is a good opportunity to rectify at least some of the sin of having forgotten him by displaying that original robe from King Lear at the new Museum of the Jewish People, which opened last week.

Since the early days of the Jewish nationalist movement, the “wise and modest language,” which was how Isaac Bashevis Singer described Yiddish, has been bickering with its younger and prettier sister – Hebrew. The rivalry over which language would be spoken by the new Jew escalated at the Czernowitz Conference in 1908 and continued from there to the language war at the Technion in Haifa. It reached a peak when violent acts were committed following the establishment of the Battalion of the Defenders of the Hebrew Language, whose members would lie in wait in dark alleys for any Jew who dared to chat in the Yiddish vernacular of the old country. This rivalry also provides the historical backdrop for our story.

In the 1920’s, there were two well-known Jewish theaters in Moscow, both of which were trailblazers, both of which enjoyed huge success, and both of which got great reviews. One of them was the Zionist Habima Theater that put on plays in Hebrew, and the other one was the Meluchisher Yiddischer Teater – the Moscow State Jewish Theater, known by its Russian acronym GOSET, whose repertory was in Yiddish.

To present the picture fairly, in those days Yiddish had a linguistic advantage over Hebrew. The Jewish story could be told better in sassy and ironic Yiddish, which was experienced in describing the way of life in the shtetl. Hebrew, on the other hand, had not yet become a spoken language and was still a flowery language, a holy language, subject to rigid Biblical syntax. When the eminent artist Marc Chagall, who was the chief set designer at GOSET, was asked to design the set for the play The Dybbuk at Habima, he said: “The actors there aren’t acting, they’re praying.” In his article entitled “The Diaspora as Tragicomedy,” Dr. Yair Lifschitz wrote the following: “for Chagall, and for others who believed in the transnational socialist dream, Hebrew was still a language that bore the weight of religious traditions, as well as the political baggage of Zionist nationalism.”

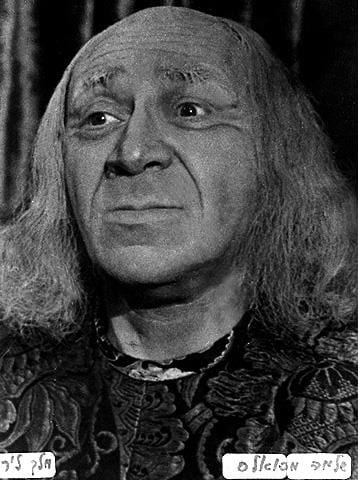

The lead actors at the two theaters also embodied the deep differences between the two cultural civilizations -Hebrew and Yiddish. On the one hand, there was the intense, pure and flawless expressiveness of Rovina, and on the other hand, there was Mikhoels – an early combination of Danny DeVito and George Costanza – who, owing to his grotesque facial features, personified the Jew from the old country, who escaped the pogroms with an ironic look on his face. Rovina was the Zionist future. Mikhoels was the ghetto-like past.

When Mikhoels played King Lear, which was the greatest hour of the Moscow Jewish State Theater, Shakespeare cried with joy in his grave. Who would have believed, the English genius most likely said to himself, that, of all people, a simple Jew who was educated in a yeshiva would succeed in playing an English king who experienced a sudden drop in status, and do so with such precision and skill. And no less in Yiddish – the language of Shylock. Having said that, perhaps the brilliant playwright would have acknowledged that a member of a people that has suffered so much loss is actually highly qualified to portray a character like King Lear. Furthermore, a tragi-comic language like Yiddish can descend to the depths of a soul of a heartbroken father whose daughters have rejected him.

The rivalry between the two theaters – Habima and GOSET – ended in 1928 when Habima relocated from Moscow to pre-State Israel. In the 1930’s, GOSET lost favor with the communist Ministry of Culture which demanded that Mikhoels – who also served as the theater’s artistic director – toe the line of the party’s realist socialism and put on fewer plays that had clear Jewish overtones.

During World War II, Mikhoels – who was considered the unanointed, but also the unchallenged, leader of Soviet Jewry – was recruited to serve on the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. As part of his duties, he traveled to the West, including to the United States. After the war, Mikhoels felt that he was being targeted by the Soviets. Rumors reached him about the party having placed him under surveillance because of his suspected ties with the West. The die was cast at an evening commemorating the celebrated Jewish writer, Mendele Moykher Sforim, which was held two weeks after the United Nations approved the Partition Plan for Palestine on November 29, 1947. In the course of that evening, Mikhoels gave a speech in which he praised the anticipated establishment of a Jewish state. From that moment on, he was marked as a traitor.

In her memoirs, Stalin’s daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva, describes the moment when her father was told about Mikhoels’s death. “Someone reported it to him and he listened. After that, he said: ‘Okay, a car accident.’ I clearly remember the tone of what he said – it didn’t sound like a question, but rather a ruling, an answer. Following that conversation, he said goodbye to me and soon after that announced: ‘Mikhoels was killed in a car accident.'” Mikhoels’s public standing and the tremendous admiration people had for him caused even a brutal tyrant like Stalin to fabricate the circumstances of his death, thereby allowing Mikhoels to have a state funeral that scores of people could attend.

A few years ago, Shoshana Mandel visited Moscow, the city of her birth. On one of the streets near the cursed Lubyanka Square, where the headquarters of the KGB were located and whose basement housed the prison where enemies of the regime were tortured, she noticed two vitrines installed on the street. One of them displayed the execution orders signed by Stalin, Beria and other arch-murderers. The other one contained photographs of some of the victims. Among them, she identified the photographs of Mikhoels and his right-hand man at GOSET, the actor Benjamin Zuskin.

When she was given the job of restoring the robe and wig worn by Mikhoels when he played King Lear, which are currently on display at ANU–The Museum of the Jewish People, Shoshana felt that she had come full circle. Even if this may be too little and too late, Mikhoels and his colleagues at GOSET are finally receiving formal recognition for their work and contribution to Jewish culture. The first lady of Israeli theater, Lia Koenig, who actually portrayed King Lear herself just two years ago, says in the museum’s special audio guide, “In some ways, all of us, Jewish theater actors and creators in Israel and across the globe, have emerged from the folds of this cloak worn by Mikhoels.” The repair has been done.