Cliché has it that Election Day is a holiday for democracy. It’s the political moment in which citizens use their mandate to shape the economic, judicial, cultural, educational future and other aspects of the society in which they live to reflect their wishes. Israel’s 71 years of democracy are just a blink of the eye In comparison to the length of Jewish history – when the definition of Jewish politics morphed time and again.

Generally speaking, the status of Jews in Islamic nations was for hundreds of years that of “Ahl al-Dhimma,” protected inferiors. In Europe, Jews were at first a “protected people,” then a “tolerated people,” and then upgraded to “beneficial Jews.” Finally, in the 19th century, they were granted equality that came with a warning: “Be a Jew at home, but heaven outside.”

It appears to many of us who graduated the Israeli school system that Jewish history is binary. The central narrative maintains that the diaspora was fraught with agonizing pain. That Jews wandered from one pogrom to another, fleeing regulations, persecutions, and mass deportation orders. And that this was all reversed by the return to Zion and the establishment of the State of Israel. From exile to redemption, Holocaust to resurrection, darkness to light. Choose your slogan – the meaning is clear. There is no lack of truth in this depiction of reality. But it is certainly not the whole truth.

One of the truths that lies on the cutting-room floor of those who edit the history of the Jewish People is the period in which Jews thrived, enjoyed extensive rights, and most important, conducted their lives in accordance with their beliefs and self-determination. We will briefly describe the fascinating and extraordinary period here in which Jews engendered an unprecedented, new and original political entity.

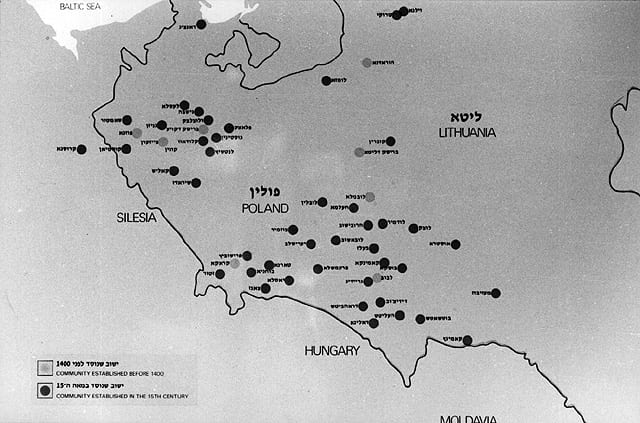

The place: The Polish-Lithuanian kingdom. The time: The 16th-18th centuries

The Jews owe the renaissance that took place during those 200 years to the feudal system that pervaded the kingdom’s political domain. During that period, the population was divided in practice into three central and non-hierarchical castes. The Catholic nobility owned estates and controlled the means of production. They had the right to purchase land and enslave groups of – mainly Ukrainian – vassals. The vassals devoted their little free time from harsh labor to hating the third caste. That caste – lower than the vassals in number but higher in the hierarchy – was the Jews.

Historian Israel Bartal describes the Jewish caste as follows: “Their spoken language is Yiddish. Their religion Judaism. They enjoy the rights of urban residents and broad communal autonomy, and the legal right to purchase urban property. A significant portion of their livelihood comes from leasing means of production owned by Polish nobility and managing the vassal work force.” The Jews were the nobility’s emissaries, the Ukrainian vassals’ bosses, and in time, the objects of the vassals’ loathing. They paid a heavy price for that in the Khmelnitsky riots of 1648, in which tens of thousands of Jews were killed.

But despite the relatively rare Khmelnitsky events, Bartal describes that period as one in which, “The status of Jews in Poland was good in every sense…They enjoyed freedom of movement and freedom to acquire urban properties, and their bill of rights granted them freedom of religion and freedom to be judged in accordance with their own laws.” It came as no surprise that by the end of the 18th century the Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian kingdom numbered nearly a million men and women, about half the Jews in the world.

So how was the political life of the typical Jewish community in Poland organized 300 years ago? Unlike Israeli elections which take place every four years, elections in large Jewish communities like Lvov, Poznan, and Krakow took place every year. The system typically called for a council of nine members comprised of community dignitaries who were obligated by protocol to have the following traits: “People of wisdom and ethics, property owners, of worthy age.” The council met annually on the Sunday of the intermediate days of Passover. They deposited a note in a ballot box bearing five names of members of their ranks. The five of nine chosen members became the “nominating committee” charged with choosing public representatives of three institutions. The first choice was that of a “community leader” or “community elder,” a would-be mayor of the community.

In order to prevent this leader’s excessive power, that choice was not limited to one candidate, but to four or five who replaced each other in a monthly rotation. The elder determined residential rights and managed the budgets of “public (see below)” institutions. He collected taxes on behalf of the Polish nobility and guaranteed loans among the community’s members. After a “community leader” was chosen, the council elected three or four “good men” to serve as acting community elders.

The next phase was the election of representatives of “public” institutions, which in our terms are equivalent to Knesset Committees. For example, the “charity gabbais” were responsible for charitable institutions like the Chevra Kadisha burial society, the Hekdesh poorhouse, the hospital, and the bathhouse. The “market elders” inspected the weights in fairground booths, oversaw the disposal of garbage from streets, and organized the roster of the “night-watch organization,” that defended the community from theft and warned them of fires. Other “public” institutions included the gabbai of Talmud Torah educational institutions, those in charge of determining Torah study times, the gabbai of the synagogue, the gabbai in charge of redeeming captive or imprisoned Jews, the gabbai of Meut Eretz Yisrael to collect donations for residents of the Land of Israel, and the gabbai moser, who mainly battled frivolous spending and flagging ethics.

The “public” institutions also managed a network of civil servant clerks, or what we now call in Israel “Deep Shtetl.” The most prominent among them was the community rabbi, who also headed its courts, organized its burials, held a monopoly on banishing and excommunicating members of the community, and also supervised the “public” institutions. Other clerks included the shtadlan, a sort of lobbyist who roamed the halls of Polish nobility in an effort to advance the community’s interests; the community darshan, an orator with a gift for rhetoric who delivered the weekly Shabbat sermon, the community scribe with a command of the Polish language spoken by boors, as well as doctors, pharmacists, midwives, etc.

The spread of Jewish residences beyond major cities gave rise to a need for an umbrella political entity to organize Jewish life throughout Poland’s regions. In about 1550, “The Four Lands Committee” was founded, which operated for 200 years and – until 1764 – served as the supreme central institution representing Polish Jewry before the authorities. The Jewish community’s aforementioned political model declined in the late 1800s after Poland was divided and the Jews were integrated in general society.