The Gemara’s Bava Metzia Tractate features a well-known argument in the annals of ethics: Two people are walking in the desert. One holds a jar containing enough water for one of them. If they divide the water between them, both will die. If one of them drinks all the water, he will survive.

Ben Peturah said: It is preferable that both of them drink and die, and let neither one of them see the death of the other. Rabbi Akiva argued that one’s life takes precedence over that of one’s fellow. A Communist in his soul, Ben Peturah preached equality until death. Rabbi Akiva – in contrast – doesn’t virtue signal, stating the obvious: A man must be true to himself. Thus, the canteen’s owner must drink all the water and live. Generally speaking, what good would it do if both died to sanctify equality?

In his book Striking Roots (Makim Shorashim), Rabbi Chaim Navon quotes renowned British philosopher Bernard Williams’s provocative words. Amplifying Rabbi Akiva’s approach, Williams says that the owner of the jar’s right to choose to drink the water takes precedence over any ethical question, as it derives from his right to selfhood. Williams cites the example of a man who sees two women drowning in a river – one of them his wife. When forced to choose which to save, the husband – any husband – would save his wife first. Not because of some learned moral ruling, but for the simple reason that she is his wife. There is a natural morality that trumps ethics. Without these special relations, says Williams, man’s identity and life would lack all meaning.

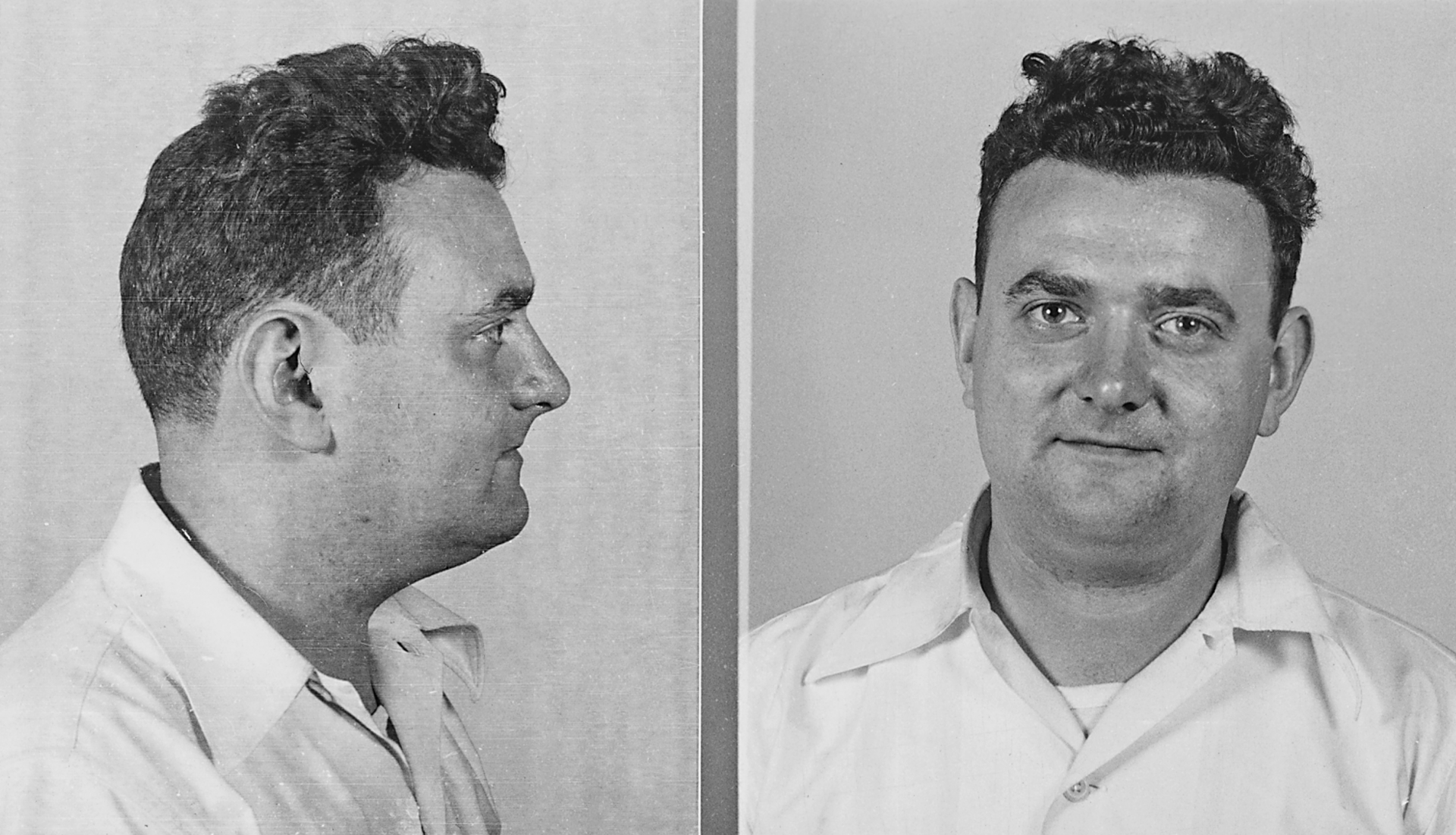

But we’re not here to enjoy ourselves. We’re here to challenge. So, let’s pose another dilemma: What would you do if one of the women drowning in the river was your spouse and the other your sister? That’s not easy. A likeable Jew, David Greenglass, faced exactly that cruel moral conundrum when he served as the central witness in the infamous 1950s affair in which alleged atomic spies Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed 66 years ago this week.

America was the scene of a new sport then – Communist hunting. Their use of uranium so went to American heads that they could not believe that primitive Soviets could produce an atomic bomb on their own. But foreign sources have it that that’s what happened. Stupid pride convinced Americans that the Russians had only managed to make the bomb with the help of classified information from the US. Before long the term McCarthyism – named after the leader of this witch-hunt Senator Joseph McCarthy – pervaded American awareness and the nightmares of every American citizen, whose linguistically-challenged lips failed to express a hint of admiration for McCarthyist doctrine in all its permutations.

In January 1950, Jewish physicist Klaus Fuchs was detained in the national campaign to contain the aforementioned comrades’ efforts. Fuchs who served on the team to develop the atom bomb at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, exposed Harry Gold to detectives as the “mule” who carried classified documents to the Soviets. In examinations, Gold exposed an array of spies – all of them Jewish – including Julius and Ethel Rosenberg and Ethel’s brother David Greenglass.

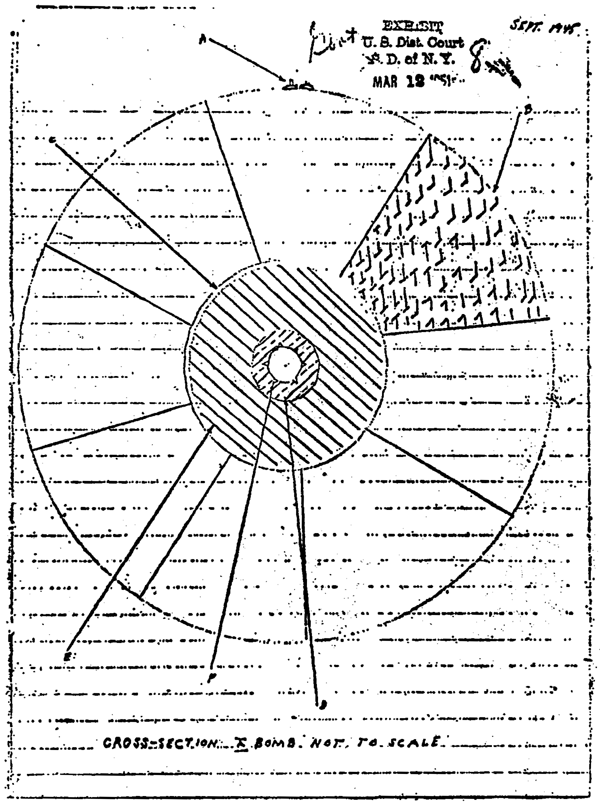

Greenglass, a humble technician in Los Alamos, hid his Communist leanings to get hired. Suspicions maintained that he had passed classified documents related to manufacture of the bomb to Julius Rosenberg, an avid Communist himself. Investigations maintained that Greenglass’s wife Ruth typed the secrets.

When he realized the investigation was closing in on him, Greenglass offered to turn state’s witness. He had yet to be tried, and his wife, the mother of two small children, faced imminent indictment for her involvement in the affair. Greenglass astounded detectives in Manhattan in 1951 when he transferred the burden of guilt from his wife to Ethel. He claimed that it was his sister – not his wife – who typed the secrets in notes. Greenglass’s dramatic testimony led to the conviction of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on espionage charges, and Judge Irving Kaufman – also a Jew – sentenced them to death.

The grave sentences sparked worldwide outrage and comparison to the Dreyfus Trial. Thinkers, artists, and writers – including Pablo Picasso, Dashiell Hammett, and Albert Einstein – sent letters to American leaders demanding that the sentences be commuted. Philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre called the sentences a “legal lynching,” and demonstrations were held around the world, including London, Paris and Rome.

But nothing helped. On June 19, 1953, the couple took the electric chair in New York’s infamous “Sing Sing” prison. The execution was expedited by several hours in response to Jewish-community pressure to avoid desecration of the Shabbat. Yes, irony also has no redlines. Julius and Ethel’s 10- and 6-year old children were orphaned. In her masterpiece “The Bell Jar,” Silvia Plath later wrote, “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.”

In the context of the plea bargain, David Greenglass was sentenced to 15 years in prison, but he was released in 1960. He spent the next four decades living a quiet life in his home in greater New York. He confessed 60 years after the execution, in 2013, that he had implicated his sister Ethel to spare his wife from justice. Greenglass added that he had no regrets. He told New York Times reporter Sam Roberts, “My wife is more important to me than my sister. Or my mother or my father, O.K.? And she was the mother of my children.” Roberts turned the series of interviews into his book “The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case.”

The solution to the moral dilemma was crystal clear – at least for a Jewish technician in Los Alamos: A wife trumps a sister.

In memory of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg