While Isaiah Berlin was on his deathbed, Oxford University dean Roy Jenkins asked if he wanted the traditional memorial service in London’s iconic Westminster Abbey afforded to the kingdom’s celebrated figures. Berlin barked, “Hell no. I’m gonna have it in the Hampstead Synagogue.”

The British Isle’s best and brightest gathered in the Orthodox Hampstead Synagogue a few days later to escort Berlin to his final reward. A colorful mosaic of Jews and non-Jews, women and men, aristocrats and public figures attended the service. Honored Lords wore kippot, and Ladies vied for space in the women’s galley. The ancient words of the Kaddish mourning prayer were chanted as Sir Isaiah Berlin, a sworn atheist, returned to his Maker.

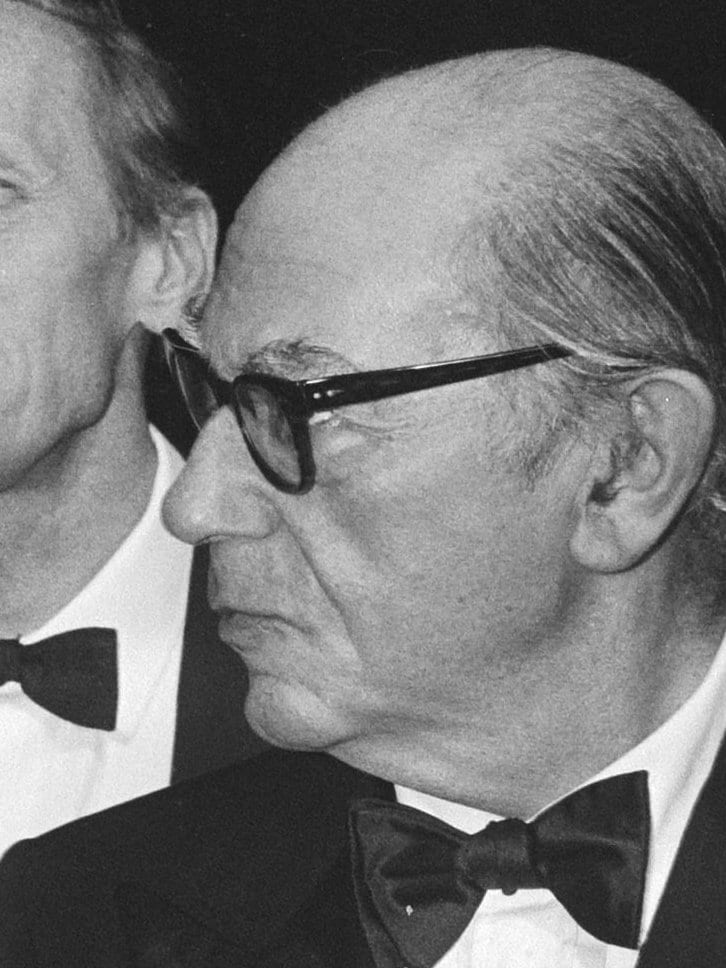

No one was surprised. Berlin’s passing reflected his life. He was a man of many contradictions, complex and eclectic, a sparkling intellectual acrobat, who was not afraid to walk a tightrope of contrary thought. How else can you explain that the greatest enemy of the totalitarian state supported the Roosevelt administration’s aggressive government involvement? How else can you reconcile the great belief in nationalism of an utterly worldly man who divided his time between New York, Washington, London and Jerusalem?

Isaiah Berlin was born in Riga, Latvia in 1909. He was the only child of well-to-do timber merchant Mendel and his wife Marie. Marie’s greatest dream was to be an opera singer, but she settled for a life within the confines of her home. Isaiah remembers her singing Bellini arias in her bathrobe when he was a child. A midwife’s malpractice during his birth caused the misshapen arm which embarrassed Berlin throughout his life. Michael Ignatieff wrote in his biography, “Isaiah Berlin: A Life” that Berlin viewed himself in general as an ugly and distorted man. That self-image led to his great fear of rejection by the feminine sex, a fear that plagued him until he lost his virginity at age 43. Two years later, he married Aline de Gunzbourg, a Russian-Jewish aristocrat with whom he had had an affair while she was still married.

Let’s backtrack a bit. The Berlin family move to London in 1921. Quickly comprehending that they were raising a singular mind, his parents sent their son to the finest private schools. After completing high school, he applied to the University of Oxford, where he studied the classics, philosophy, politics, and economics. Berlin remained at Oxford on and off for 57 years, gaining anything an intellectual could imagine from that institution. Among other achievements, he was a professor of sociopolitical theory, was knighted in 1957, received the Order of Merit in 1971, and served as the dean of the British Academy from 1974-1978.

But Berlin did not hunker down in the ivory tower. During World War II, he was an emissary to the British Embassy in Washington. Known mainly for his verbal abilities and broad horizons, the intellectual star’s reputation landed him invitations to all the right parties in the US capital. Berlin made friends in the media and connections in the highest offices of American politics, and his winning personality made him a permanent feature in the world’s most influential salons. It eventually became public knowledge that he had been invited to dine with President Kennedy at the height of the Cuban missile crisis.

His rhetorical skill was his greatest strength. Berlin spoke English with a heavy Russian-Jewish accent and terrible diction. Yet, pearls of wisdom came from his mouth. He delivered a renowned series of 50-minute lectures on the roots of romanticism in Washington’s National Gallery in 1965. The attendees aid called it a phenomenal performance and nearly super-human effort. He read the lecture from his head perfectly without notes. The lectures were transcribed as is and assembled in a book bearing the series’ name.

But he did not make do with the verbal gymnastics of one equipped with a hard drive dozens of times greater than that of a normal man. Berlin also wrote. His writing was also original, sharp, and groundbreaking. His acclaimed and rudimentary essay, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” transformed our comprehension of that term.

Berlin cited two types of liberty – one positive and one negative. He called negative liberty the absence of coercion or external force. So long as no one prevents us from doing as we wish, we are free. Positive liberty, as he defines it, is our ability to act to fulfill ourselves and our potential.

Berlin’s claim that negative liberty is positive in that it protects the individual from the tyranny of the state reflects his paradoxical contemplation. In contrast he maintains that positive liberty may actually be negative in that it can give rise to a totalitarian regime. Why? Because, for example, if a nation declares that every citizen has the “freedom of happiness,” that implies the assumption that there is such a thing as objective happiness. Then who determines what objective happiness is – the Party? The religious establishment? The social elite? This broad view of liberty is a slippery slope, because it creates circumstances in which the state can impose its view of liberty on the individual.

Berlin lived throughout the stormy 20th Century and saw the Bolshevik Revolution and the rise to power of the Nazis with his own eyes. His greatest fear was that of an “enlightened” dictatorship that pretended to represent justice and absolute morality. He believed that this could come from any political side, left or right. He died this week, 22 years ago, at age 88, leaving us a world with much more food for thought than it contained before him.

Translated from Hebrew by: Varda Spiegel